|

In 2011, with the eurozone still recovering from 2008 – 2009’s global recession, the ECB hiked rates twice—only for the economy to fall back into recession again as the eurozone’s sovereign debt crisis erupted. Many deemed the hikes a monetary mistake. With eurozone GDP growth easing to its slowest rate of this expansion in Q3, some worry the ECB’s move to reduce monthly asset purchases to €15 billion in October—and plans to end the program after December—are similarly ill-timed. If the ECB stops its monetary support, doesn’t that increase eurozone economic risks? In our view, no. Contrary to popular belief, we think the ECB’s eventual exit from quantitative easing (QE) should help, not hurt, the eurozone’s loan growth and economy—a positive surprise for eurozone stocks.

QE’s end elsewhere wasn’t a negative. Despite much fretting, prior UK and US QE exits occurred without incident. The BOE stopped its asset purchases in late 2012, and the Fed’s bond buying binge finally ceased in October 2014. Both times, many thought the UK’s and US’s economies—and financial systems—wouldn’t withstand the withdrawal. But—lo and behold!—their economies and markets didn’t implode. In 2013, UK economic growth accelerated and stocks rose. US economic growth accelerated during 2014’s tapering. In 2015, US growth slowed and stocks were flat, but this was mostly due to oil’s price collapse and its impact on investment and earnings—not QE withdrawal—which subsequent growth has proved. We expect QE’s end to go similarly fine in the eurozone.

Yet, in our view, a common misperception keeps many from cheering QE’s demise. Among the greatest tricks central banks ever pulled is convincing the world QE is stimulus. QE supposedly “works” by lowering long-term interest rates, encouraging lending. But though the “lower interest rates = more lending” theory may seem plausible, it obscures how monetary policy affects banks. Easy money requires balancing banks’ willingness to lend with folks’ desire to borrow. Banks extend loans only when profit margins make the risk worthwhile, a factor largely determined by the yield curve (or spread)—the difference between short-term and long-term interest rates. Because banks borrow short and lend long, the more long rates exceed short, the more profitable bank lending is, encouraging them to lend. By buying large amounts of eurozone long bonds, we think the ECB’s QE program lowered long-term interest rates, but it also flattened the yield curve and discouraged banks from lending. In our view, that stifled growth rather than stimulating it.

The good news, however, is the ECB has scaled back its bond purchases substantially over the last two years, helping lift long rates, lending and growth. In December 2016, the ECB first signaled its plan to reduce average monthly bond purchases from €80 to €60 billion the following April. Another taper—from €60 to €30 billion—took effect in January 2018, followed by last month’s.

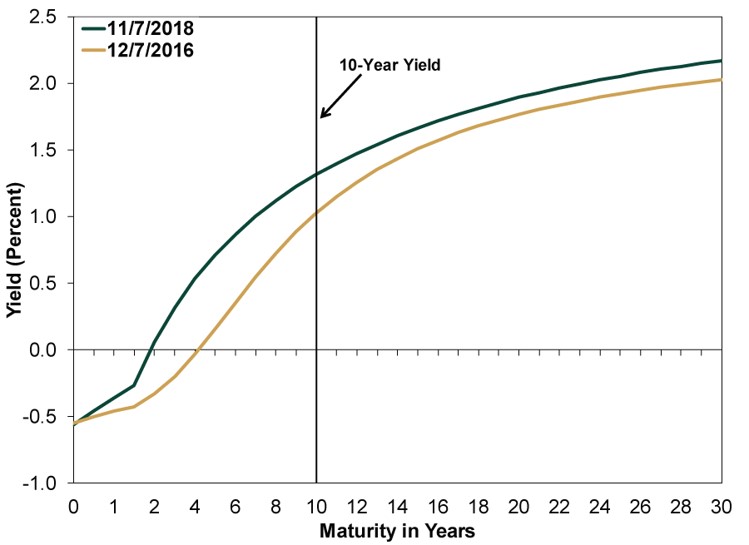

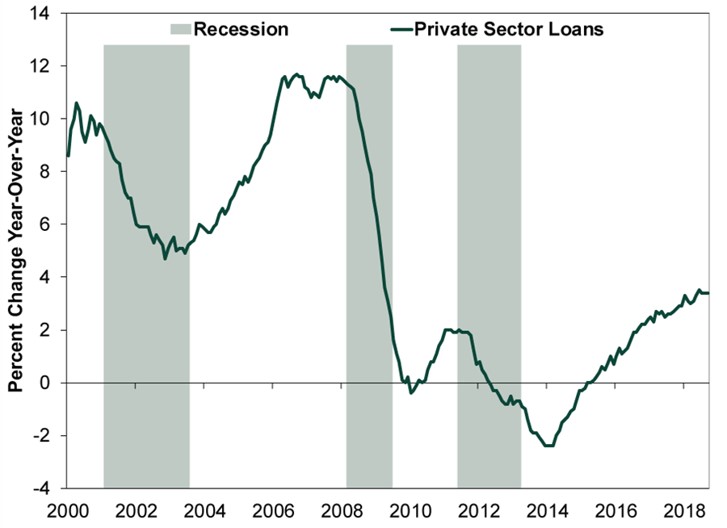

To see tapering’s impact, consider the ECB’s eurozone yield curve. Now, there is of course no collective eurozone debt—the ECB averages euro countries’ yields to calculate this as a proxy. But we believe it is a helpful, concise illustration of tapering’s impact. From the day before the ECB first broached tapering to yesterday, the eurozone yield curve spread (10-year yield minus 3-month yield) steepened from 1.6 percentage point to 1.9 percentage points.(Exhibit 1) Loan growth accelerated from 2.2% y/y in November 2016 to 3.4% as of September, which continues the upward trend from 2014 after the eurozone began its economic recovery. (Exhibit 2)

Exhibit 1: Eurozone Yield Curve Steepened as ECB Tapered

Source: ECB, as of 11/8/2018. ECB “all bonds” yield curve on 12/7/2016 and 11/7/2018. The ECB announced its first asset purchase reduction on 12/8/2016.

Exhibit 2: Loan Growth Has Accelerated

Source: ECB, as of 11/5/2018. Private sector adjusted loans (i.e. adjusted for loan sales, securitization and notional cash pooling), January 2000 – September 2018.

Despite the “stimulus” narrative, loan growth’s acceleration as the ECB has reduced bond purchases shows tapering hasn’t hurt. The ECB’s latest Q3 bank lending survey also points to easing credit standards and financial institutions’ increased willingness to lend. Rising business and household demand for and access to credit should continue driving broad economic growth.

In our view, the risk isn’t that ECB ends QE and pulls the punchbowl. We think the real risk is if the ECB overreacts to recent data by extending or even adding to QE. Markets have seemingly already been pricing in the end. U-turning now would probably extend uncertainty by creating a new round of angst over when QE would end. Returning to normal should allow people to get over it. If QE ends and the eurozone economy doesn’t tank, folks should realize the economy doesn’t need the ECB’s “support.” In our view, that would likely give investors more confidence, help improving sentiment and boost eurozone stocks. Negative sentiment surrounding QE’s end and its positive impact in reality presents a bullish disconnect—and opportunity—for investors.

|