|

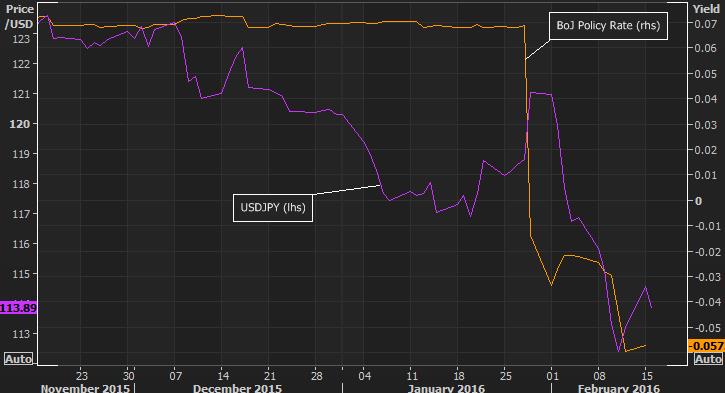

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) announced in late January that they were joining the ranks of central banks with a negative policy rate. While their policy rate did indeed go negative, as is apparent in the chart below, the amount is a modest six basis points and only a small portion of bank current account balances are subject to this rates.

The BoJ has created three categories of current account bank deposits. The Basic Balance is the average 2015 balance and continues to earn a positive 0.1% annual rate. The Macro Add-On Balance is required reserves, special credit provisions and a still-to-be determined ratio of the Basic Balance; it receives a zero rate of interest. Only reserves beyond this, the Policy Rate Balance are subject to the negative interest rate which the BoJ stated is currently about 10% of the banks’ total current account balance holdings.

It is presumed that, as the BoJ injects reserves via quantitative ease (QE), the Policy Rate Balances will gradually rise and subject banks to the negative rate. But as the ratio for the Macro Balance remains undetermined, the BoJ has a lot of wiggle room as to the breadth of reserves that will ultimately be subject to this negative rate.

Bank of Japan Policy Rate and USDJPY

Source: Thomson Reuters Eikon

What is the point of negative interest rates?

The main point of negative rates is to make it more painful for banks to hold funds on deposit with the central bank and instead deploy the funds in ways that will provide more stimuli for the economy. One anticipated avenue for banks is to push funds into foreign currency deposits where they are not subject to negative carry. The resulting currency weakness and increased trade competitiveness is one way negative interest rates can stimulate demand. In the case of Japan, though, things are not working out well on this front. As shown in the chart above, on the announcement of the headline negative rate, USDJPY spiked up testing JPY121 for the first time in over a month but the dollar’s strength was fleeting, and it has now sunk to its lowest level in over a year.

Arguably JPY strength can be attributed to the global decline in equity prices, but it still suggests that the ability for negative rates to generate currency weakness is neither strong nor reliable. The same message can be seen when looking at other countries that are now actively imposing negative policy rates. The chart below shows the profile for three other regions that have adopted negative policy rates: Switzerland, Sweden and the Euro area. Rates generally crossed the zero line for all three regions in the fourth quarter of 2014 or the first quarter of 2015 – i.e., just over a year ago. The central banks have pushed rates further negative on multiple occasions to levels that are much more significant than Japan’s headline negative six basis points. Has this generated meaningful currency weakness?

Central Bank Police Rates

Source: Thomson Reuters Eikon

Based on performance of trade-weighted currency indices shown in the chart on the following page, negative rates appear to be, at best, a fleeting source of currency weakness. CHF surged early last year when the Swiss National Bank abandoned its effort to put a floor under EURCHF and it has held that strength ever since despite the steady move of Swiss rates into ever more negative territory. The experience in Sweden and the Euro area are reminiscent of Japan. In both cases currencies initially weakened as rates went negative but then gradually recovered. Both SEK and EUR are now close to pre-zero rate levels so there is little evidence that even persistent moves into negative territory provide stimulus via weaker currencies.

Broad Trade-Weighted Currency Performance

Source: Thomson Reuters Eikon

What about domestic credit creations?

Another, and generally more important, reason that lower interest rates can stimulate demand is through increased credit expansion. To avoid paying carrying cost on reserves, banks might become more aggressive on loaning funds out either through cutting rates or extending credit to lower quality borrowers. Indeed, if policy rates turned steeply negative it might make sense for banks to lend out money at a more modest negative rate to reduce the net loss – though this is not likely any time soon. The chart below suggests that negative rates have been even less successful at stimulating credit creation than at weakening exchange rates. An expanding credit environment should increase leverage in an economy which be manifest in broader monetary aggregates rising relative to base money. There is no evidence that the move to negative rates has created any pickup in credit creation. Indeed, the downtrends of the M3 vs. M1 ratios – or deleveraging – that emerged in the Euro-area and Sweden in 2012 have continued unabated into the fourth quarter of 2015. It seems that negative rates have yet to trigger any surge in credit creation.

Ratio of M3 to M1 Supply

Source: Thomson Reuters Eikon

Janet, don't go there!

It is possible that as rates dip ever deeper into negative territory that they will eventually start having the desired result. But negative interest rates could well prove to be self-defeating. It is clearly the case that negative rates are bad news for the banking sector. Having to pay for the right to park funds at the central bank instead of earning a return is a cost to the banks which rises as rates go more negative. As shown in the chart on the following page, the impact of negative rates on bank profitability was recognized in the Japanese market. Bank stocks sold off sharply, relative to the general Nikkei decline, as the BoJ moved policy rates negative. Indeed, it was concern about impact on bank profitability that caused the BoJ to be conservative in phasing in the negative rate.

And, there is an even more adverse potential of negative interest rates. Again, the main intent of negative rates is to incentive banks to lower lending rates and, hence, stimulate credit creation. But banks may instead pass on the cost of negative rates to depositors in the form of various checking account fees. The big risk is that depositors could respond to these fees by withdrawing funds and shifting to cash. Ironically, negative rates could well spark credit contraction.

Despite the limitations and risks of negative interest rates, central banks continue to consider this as a viable policy. Apparently the Fed too is considering this as a hypothetical – the most recent bank stress test exercise included a scenario with negative Treasury Bill rates. The temptation for negative rates is that many central banks’ traditional tools have been exhausted and so there is a grasp for alternatives. But reality is not always symmetric and just because negative rates are possible does not mean they are a valid policy option.

Negative Policy Rates and Japanese Financial Stocks

Source: Thomson Reuters Eikon

|