|

In a nutshell:

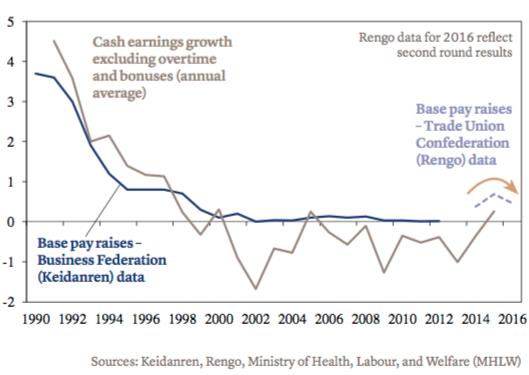

- Annual spring wage negotiations have proved disappointing thus far, increasing downside risks to inflation.

- The Bank of Japan (BoJ) could be compelled to introduce new innovative measures in April, although political and technical constraints render such a scenario uncertain.

- The Abe cabinet will likely complement the policy mix by frontloading planned fiscal expenditures – its resolve on the 2017 consumption tax hike will be tested in coming months

In Japan, March kicks off not only the eagerly awaited cherry blossom season but also collective bargaining in key industries. These annual spring wage negotiations – referred to as “Shunto” – set the tone for overall wage growth even though they only cover some 4% of the employed population. While it will take time for all the negotiations to close, early results point to meagre gains, to the tune of 0.5%.

Wage growth being a crucial cog in Japanese policymakers’ push for a virtuous reflation cycle, such disappointment, alongside recent collapses in market- and survey-based measures of long-term inflation, should make it clear that the economy demands, cyclically and structurally, sustained policy support. The problem is that the BoJ faces both political and technical constraints in pushing through further innovative measures. Its unexpected decision to introduce negative rates last January – motivated perhaps by a growing lack of Japanese government bonds available for future purchase – triggered strong backlash from both the financial industry and ordinary voters. Meanwhile, rising populist sentiment in the US, with whom Japan is working on a comprehensive trade agreement, places the BoJ in a difficult spot as regards further yen depreciation.

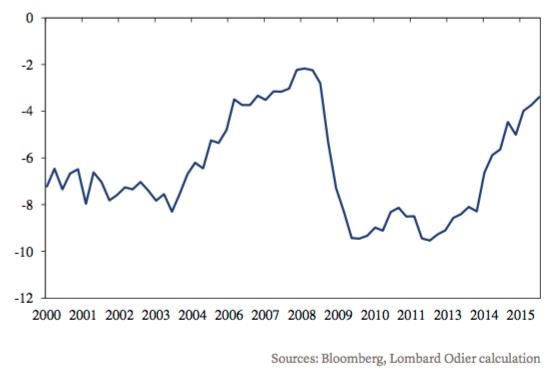

We have argued previously that fiscal policy might help solve this quandary, and it does seem that the Abe cabinet is taking steps in that direction. The recent pick-up in tax receipts allows for greater fiscal flexibility and the Prime Minister has stressed that planned spending will be as front loaded as possible. Such scheduling of disbursement could be precursor to an extra budget package mid-year, perhaps near the time of the G7 summit.

Abe continues, however, to insist that the second consumption tax hike (from 8% to 10%) scheduled for 2017 will go ahead as planned. In effect, the government will provide funding in 2016 only to take it back in 2017 – a scenario not credible in terms of its impact on domestic inflation unless the BoJ were to introduce offsetting stimulus early 2017. We actually see it more likely that the consumption tax hike be delayed again.

With Japan nowhere near the virtuous cycle targeted by Abenomics1, fiscal and monetary stimulus should eventually give way to a series of more granular and politically manageable supply-side reforms that could make a difference in the long run. The key issue is whether Japanese voters will accept to revert back to comfortable economic mediocrity, following the relatively brief spurt provided by Abe’s program. But perhaps the usefulness of Abenomics will have been to provide a workable game plan for a managed economic decline, in which bond investors pay the Japanese government to borrow.

VI. Shunto base pay raises over the last 26 years

In % yoy

VII. General government financial surplus as a % of nominal GDP

Flow of funds data, 4Q (quarter) rolling sum

[1] Abenomics refers to the pro-growth economic policies advocated by Prime Minister Abe and his cabinet, since the December 2012 general election.

Link to the original report

|