|

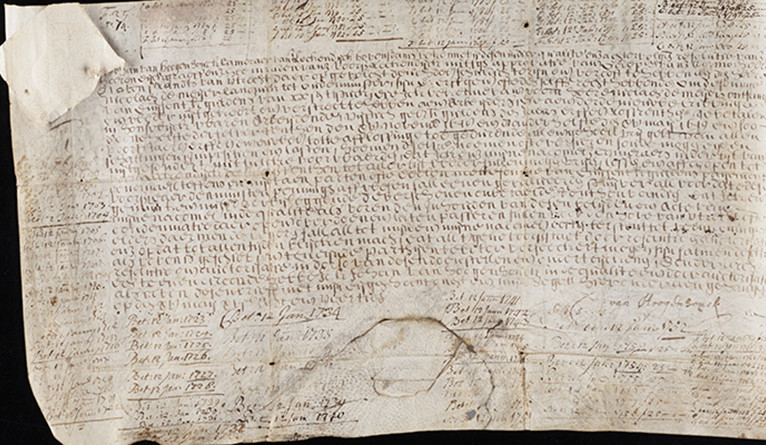

This bond was issued in 1648 by a Dutch water board to finance improvements to a local dike system. A perpetual bond, it continues to pay interest.

A 1648 Dutch water bond housed at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library is unique among the tens of thousands of manuscripts that reside there. While most of the Beinecke’s archival holdings are by their nature dead — their original purpose being fulfilled — the water bond lives on. It still pays annual interest more than 367 years after it was issued.

Timothy Young, the library’s curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts, has travelled to Amsterdam this week to visit Stichtse Rijnlanden, a Dutch water authority, and collect 12 years of interest on the bond

(http://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3435647). Collecting the back interest maintains the bond’s status as a functioning artifact from the Golden Age of Dutch finance. The water authority paid Young 136.20 euros in interest, the equivalent of $153.

“This is a teaching moment because the financial industry changes so rapidly but here we have something very old and constant,” says Young, who curates the Beinecke’s Collection of Financial History

(http://beinecke.library.yale.edu/collections/highlights/financial-history-collection) in partnership with the International Center for Finance at the Yale School of Management.

According the water authority, Yale’s bond is one of five known to exist. The bonds were issued by the Hoogheemraadschap Lekdijk Bovendams, a water board composed of landowners and leading citizens that managed dikes, canals, and a 20-mile stretch of the lower Rhine in Holland called the Lek. (Stichtse Rijnlanden is a successor organization to Lekdijk Bovendams.)

Yale’s bond, written on goatskin, was issued on May 15, 1648 to Mr. Niclaes de Meijer for the “sum of 1,000 Carolus Guilders of 20 Stuivers a piece.” According to its original terms, the bond would pay 5% interest in perpetuity.

(The interest rate was reduced to 3.5% and then 2.5% during the 17th century.)

The interest payments were recorded directly on the bond. The water board used the money raised to pay workers at a recently constructed cribbinge, a series of piers near a bend in the river that regulated its flow and prevented

erosion.

Yale acquired the bond in 2003. That year, Geert Rouwenhorst, professor of corporate finance and deputy director of the International Center for Finance, took the bond to the Netherlands to collect 26 years of back interest. That was the last time interest was collected.

“There have been many instances in history when institutions issued debt with very long tenure. In the 17th century, people sometimes issued perpetual debt. But it is very rare that there is an uninterrupted history when governments or other entities have not defaulted on those debts,” says Rouwenhorst. “Yale’s bond is an extremely early example of a security that was issued without maturity and still pays interest. One ought to be astounded that such a thing exists.”

Rouwenhorst and William N. Goetzmann, Edwin J. Beinecke Professor of Finance and Management Studies and director of the International Center for Finance, wrote a chapter about the bond “The Origins of Value,” their 2005 history of financial innovation.

They write that the Dutch water boards had relative financial autonomy, which protected them from falling fortunes of the central government and allowed the securities that they issued to survive. The lives of perpetual loans typically were “cut short by imprudent financing, government recall, or the misfortunes of wars and revolutions,” Rouwenhorst and Goetzmann write.

The acquisition of the 1648 bond raised a challenge for the Beinecke, which does not typically catalog and house “living” documents.

“The question was how to consider the status of the bond,” says Young. “In order to for the bond remain live, we need to take it to the issuing authority in the Netherlands every couple of decades to collect the interest, but unless

we’re loaning an item to another institution, we don’t allow collection material to leave the library.”

A compromise resolved the issue. By 1944, there was no longer any space on the vellum to list interest payments. A paper addendum was added to record new payments. The library permits the paper addendum to travel to the

Netherlands to collect the interest, which allows the bond to remain live.

It is a bearer bond, meaning anyone who presents the addendum to the issuing authority can collect the interest. The water board kept no register of ownership of the bond.

The Collection of Financial History also features a bond

(http://brbldl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3433724) issued circa 1622 by the Dutch East India Company, the first modern corporation. Unlike the water bond, it no longer pays interest.

|