|

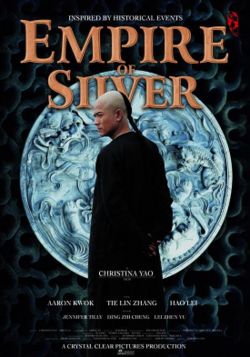

Written and directed by Christina Yao, Empire of Silver is a 2009 film of the rise and fall of the largest piaohao, "Tien chen Yuan", in the Shanxi province during the prosperous days of the Ching dynasty.

Piaohao is the name for an early Chinese banking institution, also known as Shanxi banks because they were owned primarily by natives of Shanxi.

Shanxi piaohaos established the bill of exchange that took over the more custom way of waiting for the money to be transported from one's original piaohao. But Chinese financial institutions were conducting all major banking functions, including the acceptance of deposits, the making of loans, issuing notes, money exchange, and long-distance remittance of money.

The film is about a wealthy banking clan and its fortunes during the turn-of-the-century China. The country is in the midst of great change. Paper money is replacing the need to hoard silver; the pro-nationalistic, anti-foreigner Boxer Rebellion unrest takes hold; the centuries-old Chinese dynasties are dying; invasions are afoot.

The piaohao which also includes saving services also controlled the country's economy, which is known as the antecedent of today's banking system, and the Tsin merchants soon became popular. At the height of power and splendors of Tien Chen Yuan's business, it had 23 sub-branches located in various places in China, Russia, Mongolia, Japan and the Malay Archipelago area, its wealth was enough to control the country's economy.

The owner of this piahohao empire Master Kang led a group of chief managers and branch managers that had successfully contributed to his business. Their business ethics seems to have distinguished them from tother merchants, as their partnership endures through robbery, run on a bank, Boxer Rebellion, struggle for benefits between government and civilians, and the 1911 Revolution!

Among the highlights of the film that might be of interest to investors:

As rumors spread that a bank was running out of silver, customers began to retrieve their savings at once and unleashed a run on the bank .

When an armed convoy carrying heavy coffers of silver finally arrived, depositors regained confidence in the institution. But behind the facade, bank officials opened the cases that were effectively filled with...stones ! The belief among the public that there silver has been delivered was enough to regain its trust!

According to Linsun Cheng (Banking in Modern China, Cambridge University Press, 2003):

“The first piaohao originated from the Xiyuecheng Dye Company of Pingyao. To deal with the transfer of large amounts of cash from one branch to another, the company introduced drafts, cashable in the company's many branches around China. Although this new method was originally designed for business transactions within the Xiyuecheng Company, it became so popular that in 1823 the owner gave up the dye business altogether and reorganised the company as a special remittance firm, Rishengchang Piaohao. In the next thirty years, eleven piaohao were established in Shanxi province, in the counties of Qixian, Taigu, and Pingyao. By the end of the nineteenth century, thirty-two piaohao with 475 branches were in business covering most of China.

All piaohao were organised as single proprietaries or partnerships, where the owners carried unlimited liability. They concentrated on interprovincial remittances, and later on conducting government services. From the time of the Taiping Rebellion, when transportation routes between the capital and the provinces were cut off, piaohao began involved with the delivery of government tax revenue. Piaohao grew by taking on a role in advancing funds and arranging foreign loans for provincial governments, issuing notes, and running regional treasuries.”

The author goes on...

"By the end of the nineteenth century, thirty-two piaohao with 475 branches were in business covering all of China's eighteen provinces, plus Manchuria, Mongolia, Xinjiang, and other frontier areas. As the spread of banditry endangered the shipping of silver bullion, the piaohao's remittances became more valuable and more convenient for merchants.

Where an armed convoy of silver would cost 2 to 3 percent of its value, the piaohao usually charged only three-tenths of 1 percent for drafts. The effectivenes and safety of the piaohao's services earned it a first-rate reputation and attracted increasing numbers of clients.

Starting in the 1860s, piaohao further became involved with official businesses through the delivery of part of the government revenue. In accordance with Qing government ordinances, certain provinces had to submit part of their tax obligations, called "jinxiang", directly to China's capital, Beijing. Since most revenues of the central government came from jingxiang, the Qing court had strict regulations regarding its collection and shipping.

All jinxiang had to be sent as silver in special packages under official escort. The local officials were not allowed to use private services for the jingxiang's shipping. The system was kept intact for more than 200 years."

|